Cycling Guangxi 21-Lingqu

At 2:45 pm, I rode to Xing’an County, where Guo Moruo’s comments were engraved on the pillars: “There is the Great Wall in the north and the Lingqu Canal in the south.” It should be from Jia Yi’s “On Passing the Qin Dynasty.”.

Drop your luggage at the hotel and hurry to Lingqu Scenic Area, the third batch of national cultural relics protection units announced in 1988.

Not far from the entrance is the Sixian Shrine, which was once transformed into a cultural relics exhibition room, but now it has been converted back to the Sixian Shrine to worship Shi Lu, Ma Yuan, Li Bo, and Yu Mengwei.

Shi Lu built the Lingqu Canal, while Ma Yuan was said to have dredged the Lingqu Canal during the Jiaozhi expedition.

Li Bo built a steep canal, and Yu Meng Wei built a steep one.

According to the “Records of the Baiyue Sages”, “Lu was appointed as the governor of the Qin Dynasty.” History was an official position, and Lu was named after him.

Historical records only mention this, and later generations can only call him Shilu.

Xing’an is high in the southeast and northwest, and low in the middle.

The southeast is Haiyang Mountain, the northwest is Yuecheng Ridge, and the middle is the Xianggui Corridor.

Xing’an is located in the watershed between the Xiangjiang River in the Yangtze River system and the Lijiang River in the the Pearl River system.

The Xiangjiang River flows north and the Lijiang River flows south.

The closest distance between the Haiyang River, the source of the Xiang River, and the Shi’an River, a tributary of the Li River, is only 1.7 kilometers, but the height difference between the two rivers is a full 7 meters.

How to make one river rise 7 meters higher than another? This may be easy in modern times, but the hydraulic engineering of the Qin Dynasty did not yet master such technology.

Fortunately, the height difference between the two rivers near Linyuan Ridge is only 1.1 meters.

As long as a small water retaining dam is built and the hard rock walls of Linyuan Ridge are utilized, the ocean water can be diverted to Shi’an Water.

Lingqu has experienced more than 2000 years since its birth, with dozens of recorded major repairs.

It is unknown what it looked like when it was created and at the initial stage of operation, but it can be navigated and transported in large quantities.

It can be speculated that Lu at least completed the water retaining dam project along the Xiangjiang River, which was later called the balance of size, and excavated a channel to communicate with Shi’an River.

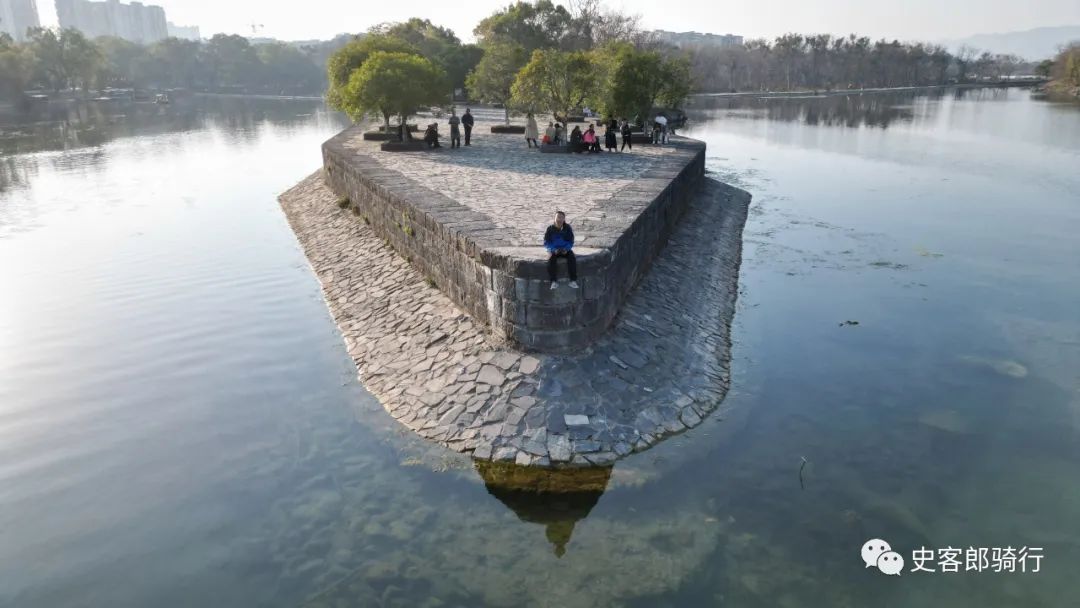

The large and small scales are the core of the Lingqu Canal, and the ones inclined towards the southern canal are called the small scales, which are 127 meters long; Inclined to the north channel is Dapingping, with a length of 343.3 meters.

The large and small scales cut off the Haiyang River and formed a small reservoir: the magnesium pond, which solved the height difference between the two major water systems.

The arm lengths of the small scale, the large scale, the magnesium pond, and the Huazui scale are related to the water diversion ratio of the Lingqu Canal.

During the wet season, the floods that need to overflow on the north side far exceed those on the south side, so the large scale is longer.

However, in order to achieve a water division of (south) three (north) seven, it is mainly achieved by adjusting the slope and curvature of the channel.

The short north channel is the key to adjustment.

From the existing north channel, there are two 180 degree bends, ingeniously extending the channel and reducing the flow rate.

The tortuous North Channel is one of the keys to Lingqu’s ability to achieve navigation more than 2000 years ago and still maintain a proportional distribution of water.

The riverbed of the Haiyang River is filled with sand and pebbles, making it difficult to build a dam to stabilize it.

The ancients skillfully used the simplest techniques and materials to achieve this: driving piles with pine trees 2 meters long, then laying a layer of pine trees horizontally between the piles, filling the piles with sand, mud, and pebbles, and then laying stones, making “pine trees soaked in water will not rot for a thousand years.”.

The falling surface is built into a 10:1 slope shape, with long pieces of rubble inserted directly and scales arranged vertically, which is called a fish scale dam.

Water rolls and falls on the slope, reducing the impact force by 80%, reducing the impact and hollowing damage of the torrent to the dam bottom.

“Paving huge stones on the dam crest was limited by mining and transportation conditions at the time, and the stones for dam construction should not be too large.

Technicians chiseled riveted grooves in the abutted stones, and poured molten pig iron to secure the stones together, forming a rigid whole.”.

The same damming technology can be seen in the Yuan Dynasty sluice discovered in Shanghai, which conforms to the specifications of the Song Dynasty’s “Construction Method”.

However, the fish scale dam technology was not mature until the Ming Dynasty, and it was impossible for Shi Lu of the Qin Dynasty and Li Bo of the Tang Dynasty to adopt it.

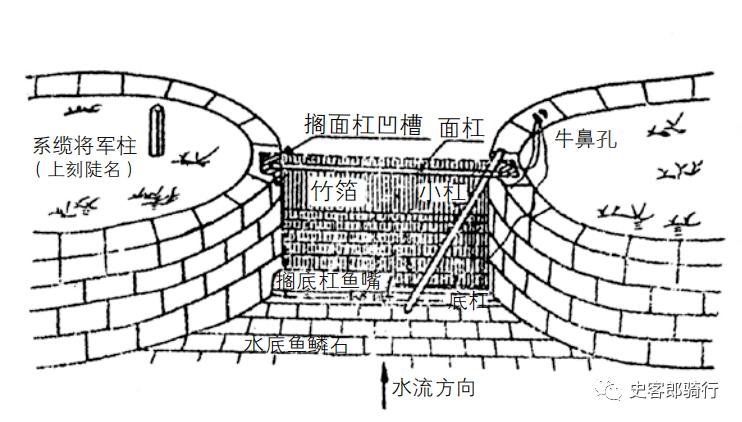

“The moldboard is an auxiliary facility for measuring scales.

The earliest record was made in the Tang Dynasty.

It has a sharp front and a blunt back, forming an unequal quadrilateral shape, with sharp corners at the top, and can serve to smooth the flow of water, divert water, and guide navigation.”.

In 1975, an ancient level measuring instrument was unearthed near Tianpingba.

The top of the stone column was chiseled with a notch, and the column body was chiseled with a square hole.

The measurement method is as follows: erect a marker post at the same distance between the large and small Tianping dams, insert a wooden rod through the hole below the stone pillar to rotate the stone pillar, and find an equal horizontal point through the hole groove above the stone pillar to construct, so that the large and small Tianping dams are basically maintained at the same horizontal height.

This ensures that the balance “scales the water up and down, appropriately” the role of backwater and overflow.

Ask Pan Yue and he confirms that this is similar to the principle of modern level testing instruments.

The three major water conservancy projects of the Qin Dynasty: the Zheng State Canal, which took the entire country of the Qin State’s strength and took ten years to complete; Dujiangyan Irrigation Project, with the strength of the whole county of Shu, took three years; The Lingqu Canal was built under the supervision of Shilu alone, using part of the manpower of the Expeditionary Army, and was completed in less than a year.

The Lingqu Canal built by Shi Lu was the earliest form of the canal, and it could not be very complete.

It barely connected the Xiangjiang and Lijiang river systems.

It is likely that most of the materials still needed to be carried by expedition soldiers to cross mountains and mountains, which had limited impact on the Qin State’s conquest of Lingnan.

“The event of” Pingnan Yue “is comparable in the historical data of the Qin Dynasty and later generations, but there is no record of Lingqu, nor is there a” Le Shi “used by ancient people to record merit.”.

The perfect and great water conservancy project seen today should be the accumulation of various dynasties and generations over the past 2000 years.

The dredging of the Lingqu by Ma Yuan is basically a legend, and judging from the current situation of the Lingqu, dredging is unnecessary.

If there is any basis for the legend, it just shows that the original Lingqu structure is far from complete.

The earliest record of the emergence of the steep gate of Lingqu was in the first year of the Baoli reign of Emperor Jingzong of the Tang Dynasty (825), when Li Bo was appointed governor of Guilin and presided over the renovation of Lingqu.

Compared with modern sluice gates, Dou has a significant difference in morphology, but its functions and principles are identical.

Li Boxiu’s steep slope was a simple bamboo and wood structure, and due to poor supervision due to illness, a major overhaul was carried out several decades later.

The moderator was Yu Mengwei, who began serving as the governor of Guilin in the ninth year of Xiantong’s reign (868).

.